History of Urban Smart Growth’s CEO open to question

Photo credit/ Manfid Duran

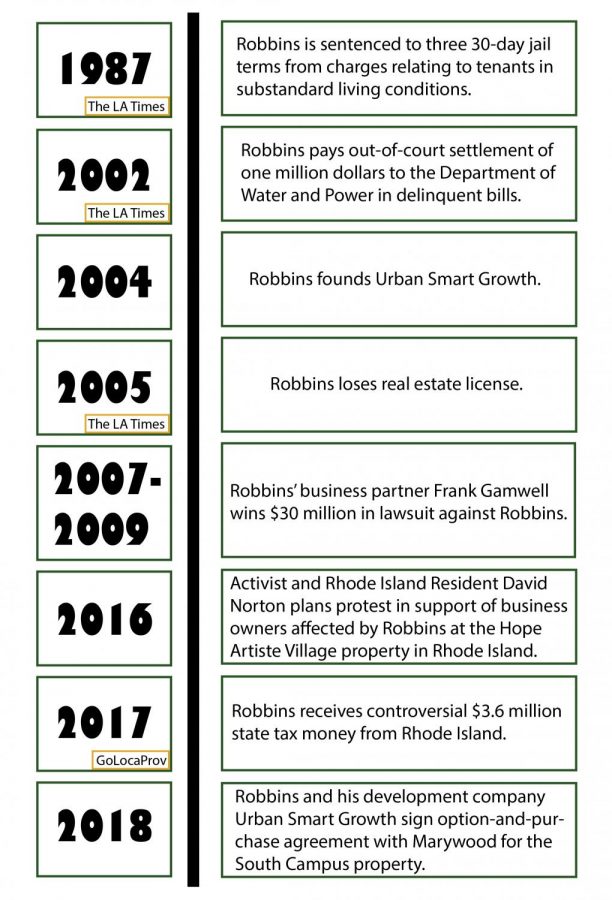

Marywood University signed an option and purchase agreement with Urban Smart Growth and CEO Lance Robbins on Jan. 3.

April 9, 2018

Lance Robbins, the CEO and founder of the development company that signed an agreement for Marywood’s South Campus, has had a questionable history in his real estate career and development projects across the country.

Marywood signed an option and purchase agreement with Urban Smart Growth, a Los Angeles-based real estate development and management company, on Jan. 3. The company revitalizes old buildings and has worked on 54 properties in six states, according to its website. Robbins founded Urban Smart Growth in 2004.

The Wood Word spoke with Robbins, Marywood President Sr. Mary Persico, IHM, Ed. D. and individuals who have dealt with Robbins in the past to investigate the potential impact Robbins’ development of the South Campus property may have on the community.

Robbins’ past in Los Angeles

According to two articles from The Los Angeles Times published in the 1980s, Robbins faced 20 criminal counts relating to slum conditions in Los Angeles apartment buildings where he was the landlord. He was sentenced to three concurrent 30-day jail sentences and pleaded no contest to the charges, which included violations of health, fire and safety codes.

The Los Angeles Times reported Robbins acquired more than 1,000 apartment units throughout Los Angeles between 1981 and 1985. In the reporting, The Los Angeles Times described him as “a landlord with one of the worst records of slum housing violations in Los Angeles.”

Additionally, in 2002, Robbins was required to pay $1 million in delinquent Department of Water and Power bills and over $200,000 to a tenant group in Los Angeles.

The Wood Word spoke with Lauren Saunders, now the associate director at the National Consumer Law Center in Washington D.C., who was in charge of a slum-housing conditions project at a legal services organization in Los Angeles at the time of Robbins’ violations. She represented tenants who were living in apartments in uninhabitable conditions.

“His buildings were constantly coming to my attention for being in deplorable conditions,” she said.

According to Saunders, Robbins was one of the biggest owners of slum-housing properties and did not comply with the city’s orders. She added that he used creative legal maneuvers to avoid prosecution and paying bills.

“It was incredibly inventive in the ways he committed fraud on the system,” Saunders said.

During her time working in Los Angeles, Saunders said she went inside some of Robbins’ properties and saw cockroaches, mice, rats, electrical issues and leaky plumbing.

“I would be very worried to engage with him,” she said. “In my experience, he was absolutely willing to skirt the law and neglect his properties and come up with devious ways to avoid responsibility.”

Robbins’ side of the story is different. He said Los Angeles was in an “economic freefall” in the 1990s. He added that the government came to him with thousands of apartments and asked him to clean them up.

“The federal government and banks and partnerships came to me like mad and said these buildings are abandoned, banks had failed and federal bureaucrats had no ability to run this stuff,” Robbins said.

According to Robbins, the controversy stemmed from buildings that were set up to fail. He said during this time period, building inspectors were told not to sign off his buildings.

“I had precipitated a lot of political controversy because I got legislation passed to compromise rent control in return for bringing investment capital into these buildings,” he said.

Robbins added that building code violation was a strict liability. He said if a light burned out on an exit sign or if a fire exit door was blocked by a tenant overnight it was considered a crime. He emphasized that, ultimately, all of his projects were completed.

In 2005, the state of California revoked Robbins’ real estate broker’s license. Robbins cited the strict building code violations as the reason for losing his license.

“Even though it takes no intent to have a violation, it will cause that license revocation,” he said.

Robbins also has attorney status in California. There are seven court dockets relating to Robbins’ work as an attorney between the years of 1988 to 2010, according to The State Bar of California. His attorney status is currently active, but he was not able to practice law for a time period in both 1996 and 2011. He was not eligible because he did not pay bar member fees and did not comply with minimum continuing legal education (MCLE).

Former business partner sues Robbins

In 2009, Robbins’ former business partner Frank Gamwell, who now works for Project Construction Management in Los Angeles, was awarded $30 million in a lawsuit against Robbins.

According to Gamwell, the lawsuit started in 2007 and was settled by 2009. He said an arbitrator awarded him $20 million in damages and attorneys’ fees and $10 million in punitive damages.

Robbins said this lawsuit was a civil dispute between two partners who got in a fight.

“I lost an arbitration. We ended up fighting it out in court. We ultimately settled it up and are done,” he said.

Gamwell said that the product Robbins produces is very good, but “to get it done he creates a wake.”

Robbins’ work in Rhode Island

In more recent years, Robbins began a mill restoration project in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, called Hope Artiste Village. In 2017, Robbins received $3.6 million in taxpayer money from the state of Rhode Island for an addition to this property.

Members of the community near the Hope Artiste Village property protested against Robbins receiving the money based on his past reputation. Business owners participated in the protest and alleged that Robbins bankrupted them when they leased space in the Hope Artiste Village property.

David Norton, a self-described activist in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, planned the protest. He said bankrupted business owners reached out to him about their involvement with Robbins. He had the idea to make signs and protest in front of the buildings at Hope Artiste Village.

“The problem that I have with this guy in my community is that I know that he is a bad actor,” Norton said.

Robbins explained that the business owners “did not pay their rent [and] that’s why they were evicted.”

Norton said his advice to other communities is to “stay away” from Robbins and research what he plans to do with respective properties.

Robbins is still pursuing the tax credit and according to Communications Deputy Director Brian Hodge from the Rhode Island Commerce Commission, a mediator is in place for the tenants involved in the addition of the Hope Artiste Village property.

Timeline of Robbins real estate and development history

Marywood president comments on Robbins

Marywood President Sr. Mary Persico, IHM, Ed.D, said Robbins brought these past issues to Marywood’s attention. She said Robbins wanted Marywood to know about these issues before hearing them from someone else.

“He sent us a little matrix so to speak with all of the issues on one side of a table and then all of the resolutions on the other side of the table,” she said.

According to Persico, Robbins was able to explain everything that happened.

“He didn’t try to deny it. He tried to talk about how they learned lessons from it and how they went about resolving the issues,” Persico said.

She added that one of the members of the Board of Trustees was simultaneously uncovering some of these issues when Robbins told the university they may find information if they searched his name online.

Robbins said he thinks university administrators feels he’s a “fairly reliable guy” after looking at his over 20 years of project experience.

Members of the Green Ridge Neighborhood Association (GRNA) met on March 13 to discuss the plans for South Campus. GRNA President Mark Seitzinger said one of his issues with Urban Smart Growth potentially purchasing the property is Robbins’ reputation and the past lawsuits against him.

If any members of the Green Ridge community have questions or concerns, Robbins said he has a blog where he can be reached and is frequently visiting Scranton.

“If anybody wants me, they can just talk to me,” he said. “No one has mentioned this [reputation issue] in the 110 surveys or emails we got.”

Persico said as of now, Marywood has a good relationship with Robbins and Urban Smart Growth. However, she said if the university sees Robbins or his company treating people unfairly, it could affect the deal.

“I think they’ve been very transparent, but we’re not going to be stupid about it,” she said. “We’re going to really pay close attention to what’s happening and make sure everything is on the up and up.”

Contact the writer: [email protected]

Twitter: @RLookerTWW